This essay was written to acknowledge the films 30th Anniversary (22nd September 1995)

The vision of New York presented in David Fincher’s 1995 cult classic Se7en is one that remains relevant today. Endless fights between neighbours penetrate the paper-thin tenement walls, while an oppressive and seemingly never-ending rain beats down on its grizzled, hopeless citizens.

The film often unfolds during the daytime, yet somehow still manages to be one of the darkest depictions of inner-city life ever put to film. The city itself is as terrifying as the unknown killer, and each new crime scene our detectives encounter is a stark reminder of the brutal setting.

There’s an argument that the events of the film couldn’t happen in any other city; only New York could drive a man to such unspeakable acts.

The city’s suffocating atmosphere is not just a backdrop — it is a character in itself. The way the camera lingers on the dreary streets, the endless rain, and the decay seeping into every corner of the filthy city is oppressive beyond belief.

It’s almost more akin to a comic-book depiction of a city. And it is one of the factors that makes Se7en so haunting.

The city seemingly reflects the sinful nature of its inhabitants. It doesn’t just house the horrors, it incubates them.

The film has lost none of its impact thirty years after its initial release. It is still one of the greatest thrillers ever made.

Detective William Somerset’s (Morgan Freeman) disillusionment with inner-city policing remains a powerful narrative tool. His absolute hopelessness mirrors the killer’s own.

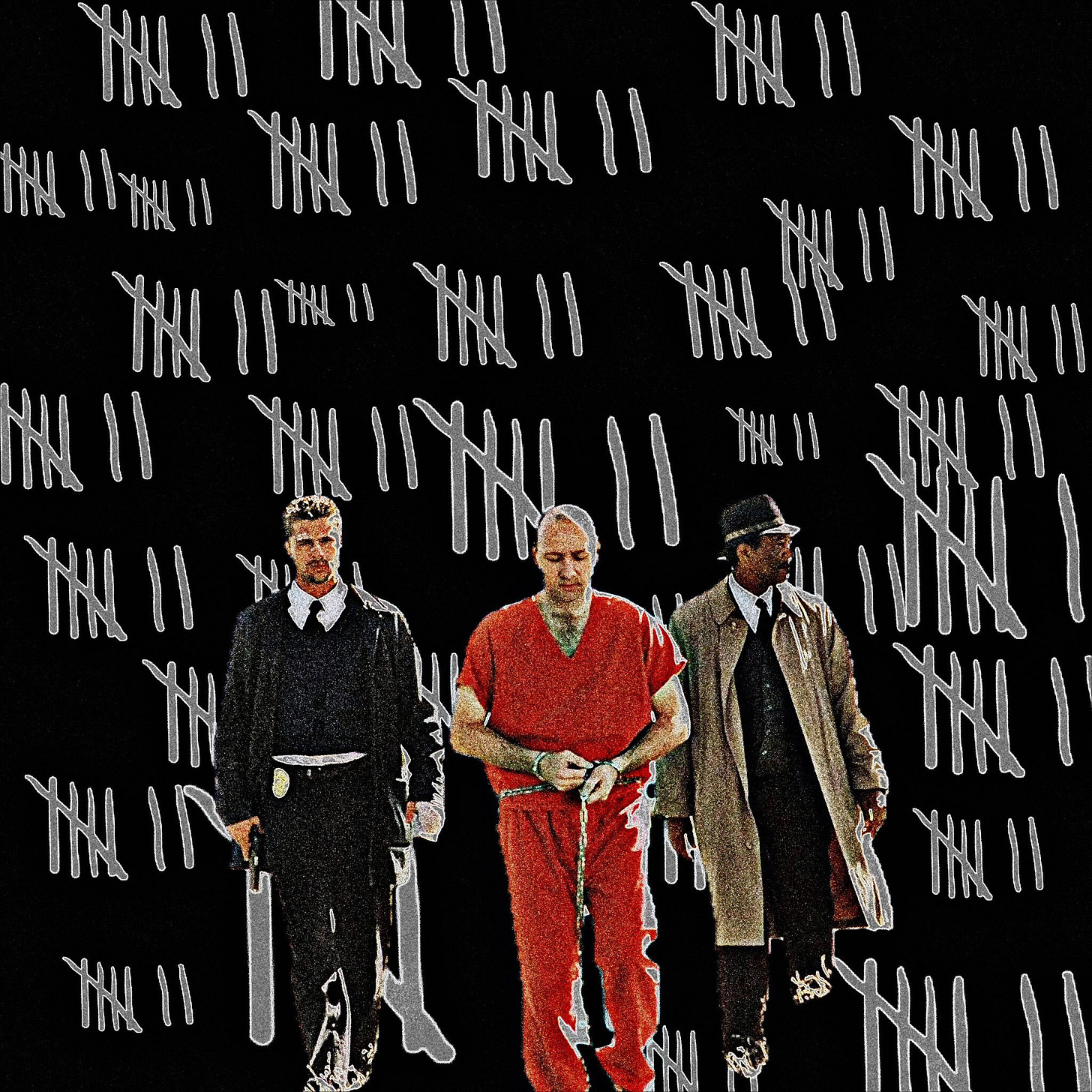

Scenes that linger on his dejected expressions are just as chilling now. One striking example comes when his new partner, David Mills (Brad Pitt), cannot remember the name of a fellow cop he witnessed being shot in the line of duty.

Somerset is a man completely out of patience and understanding. He cannot relate to his new accomplice’s apparent optimism and desire to make a change.

It’s the old versus the new. The disillusioned realist versus the idealistic believer.

It’s no accident that the film begins with Somerset’s impending retirement. His resignation isn’t just from the force, but from the idea that there’s any real justice to be had in the world.

Detective Somerset and the film’s mysterious killer are also well-educated and, as a result, well-read.

The film is steeped in literature, with the killer referencing works such as Dante’s Inferno, Paradise Lost, and The Canterbury Tales. Somerset then invokes these same texts with his partner in their efforts to crack the case.

These literary references suggest that the killer isn’t just an unhinged madman, but a deeply intellectual figure — someone who perceives the world through the lens of divine retribution.

This is where Se7en differs from the average detective story. It introduces a villain with intellectual depth.

The killer’s acts aren’t just random; they are (in his mind) a twisted kind of justice.

One often overlooked fact is that the killer appears to have Catholic leanings. By proxy, he must be counted among the more disturbing fictional Catholic characters of all time.

His religious fervour, intertwined with a desire for penance, gives his crimes a sense of ritual. And that’s what makes him truly terrifying. He’s not just a serial killer; he’s a man carrying out an unholy crusade, believing he’s delivering a twisted salvation upon a modern equivalent of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Further evidence of this unique strain of guilt is that the killer seems to want to be caught and punished. He leaves clues for the detectives to locate crime scenes, as well as a trail directly to himself.

Later in the film, he declares himself guilty and unimportant. He is surprisingly lacking the usual ego and megalomania of on-screen serial killers.

He’s a man consumed by his own guilt. This guilt is demonstrated in his actions, from the brutal murders he commits to his own eventual surrender and judgment via the state.

He also seemingly exhibits some homosexual inflections in his voice and mannerisms, pointing toward a more conflicted killer than we are used to. It’s one of those subtle character traits that adds an extra layer of unease to the film — a man at war with himself.

He’s seeking redemption, but it’s a redemption that’s as twisted as the city he inhabits.

Although Somerset claims he is “just a man,” he is evidently an extremely complex one.

And not, as Detective Mills adamantly claims, “simply crazy.”

The film blurs the lines between good and evil constantly. The killer is not one-dimensional. The same goes for Somerset and Mills — they are both in a constant battle between their ideals and the corrupt world they live in.

When questioned by his superior about why he can’t quit the force, Detective Somerset recounts a ghoulish story of a man being stabbed in both eyes. The story mirrors the killer’s own disgust with the city.

It sounds like it could have been written in one of the killer’s countless hand-scrawled diaries.

Both Somerset and the killer hate the city, yet continue to live there. Somerset even accidentally champions the killer in a scene where he and Detective Mills unknowingly come across him in disguise in a hallway.

Throughout the film, you realize at multiple points that Somerset and the killer are two sides of the same, filth-ridden coin.

It’s this duality that makes the film more engaging and thought-provoking, similar to the dual father figures in a film like Platoon.

The chase through the hallway/disguise scene is a key point in the film.

It ends with the killer letting his pursuer (Detective Mills) live, instead of shooting him at point-blank range.

This is obviously because he has grander plans for Mills himself. But the outcome of this chase (the killer getting away) has catastrophic consequences for Detective Mills.

Not only is the killer free to kill again, but he now has the upper hand. He has acted as a god himself, gifting Mills his life when he could have so easily taken it away.

As Detective Somerset puts it toward the end:

“John Doe has the upper hand!”

The film has none of the cheese you frequently find when revisiting films from the nineties (barring a one-liner about a dead dog). Instead it occupies its own extremely dark place in cinema history.

I imagine seeing this in the cinema in 1995 must have been nothing short of mind-blowing.

The film went on to influence a boatload of modern gritty detective dramas, thrillers, and horrors. Most of them failed to recreate the unique atmosphere of Se7en.

It catapulted Fincher well into the Hollywood mainstream after a difficult production history and allowed Brad Pitt to take on less “pretty-boy” roles.

It’s a film that is actually better on repeat viewings, as it reveals more of itself each time to the viewer.

Se7en’s psychological realism has since been imitated, but never quite matched. It redefined what a thriller could be, with its slow-burn tension, disturbing imagery, and moral complexity.

It pushed the genre into darker, more philosophical waters.

It wasn’t just about “whodunnit,” but why they did it, and whether any of it could ever truly be understood. In much the same way society considers real serial killers, rather than the simplistic ‘bogeyman’ of old Hollywood.

David Fincher gave birth to a new kind of thriller — one less about the spectacle and more about the creeping, nameless dread of what hides beneath the surface.

It’s a film that continues to haunt the viewer long after the credits roll.